When people talk about 1940 nickel value, they often expect a simple answer: “It’s old, so it must be worth a lot”. The truth is far more interesting. The Jefferson nickel, introduced just a couple of years earlier in 1938, quickly became one of the most familiar coins in American pockets. By 1940, the design had already settled in as the standard five-cent piece, but that year’s issues carry stories that still attract collectors today.

The 1940 nickel isn’t rare in the way gold coins or early colonial coppers are, yet it holds a special charm. Some examples remain common pocket change relics worth only a few cents, while others reach strong prices at auctions and coin shows. The key difference comes down to details: where the coin was minted, how well it has survived, and whether it hides unusual features. For anyone who has stumbled across one in an old jar, knowing what makes it special is the first step toward unlocking its real value.

The 1940 nickel belongs to the Jefferson series, with a familiar portrait of Thomas Jefferson on the obverse and his Virginia home, Monticello, on the reverse. The design was created by sculptor Felix Schlag, and though it has been updated over the decades, the basic layout remained the same for much of the 20th century.

That year, the United States Mint produced the nickel at three different locations:

Philadelphia: No mint mark, with approximate figures of 176,485,000 pieces

Denver: Mint mark “D”, with approximate figures of 43,540,000 pieces

San Francisco: Mint mark “S”, with approximate figures of 39,690,000 pieces

These marks can be found on the reverse, to the right of Monticello. Many new collectors overlook this small detail, but it is one of the most important factors when determining value.

The coins were struck from the traditional alloy of 75% copper and 25% nickel, the same metal mix used since the introduction of the five-cent piece in 1866. Only a couple of years later (during World War II) the composition changed to include silver, but in 1940 the nickels were still made of the original blend.

An interesting fact: the 1940 nickel had a very high mintage. Millions were produced, which is why circulated examples are still fairly easy to find. Yet within this large pool, coins in pristine condition or those with rare striking errors are much scarcer. That is where the real excitement begins for collectors.

Despite the high mintage, these coins no longer circulate in everyday commerce. Their worth now depends on collector demand, condition, and mint mark. While well-worn pieces may fetch only a small premium over face value, higher-grade examples are sought after.

A circulated 1940 nickel from Philadelphia might sell for less than a dollar, but an uncirculated one graded MS65 can easily bring $20 or more. Coins from Denver and San Francisco often reach slightly higher premiums, especially in better grades. Add an unusual minting error, like a doubled die or an off-center strike, and the price can jump far beyond what most people expect from a “nickel”.

Grade / Condition | Philadelphia (No Mark) | Denver (D) | San Francisco (S) |

Good (G-4) | $0.10 – $0.20 | $0.20 – $0.40 | $0.20 – $0.50 |

Fine (F-12) | $0.25 – $0.50 | $0.50 – $1.00 | $0.60 – $1.20 |

Extremely Fine (XF-40) | $1.00 – $2.00 | $2.00 – $3.00 | $2.50 – $4.00 |

Uncirculated (MS-60 to MS-65) | $4.00 – $20+ | $6.00 – $25+ | $8.00 – $30+ |

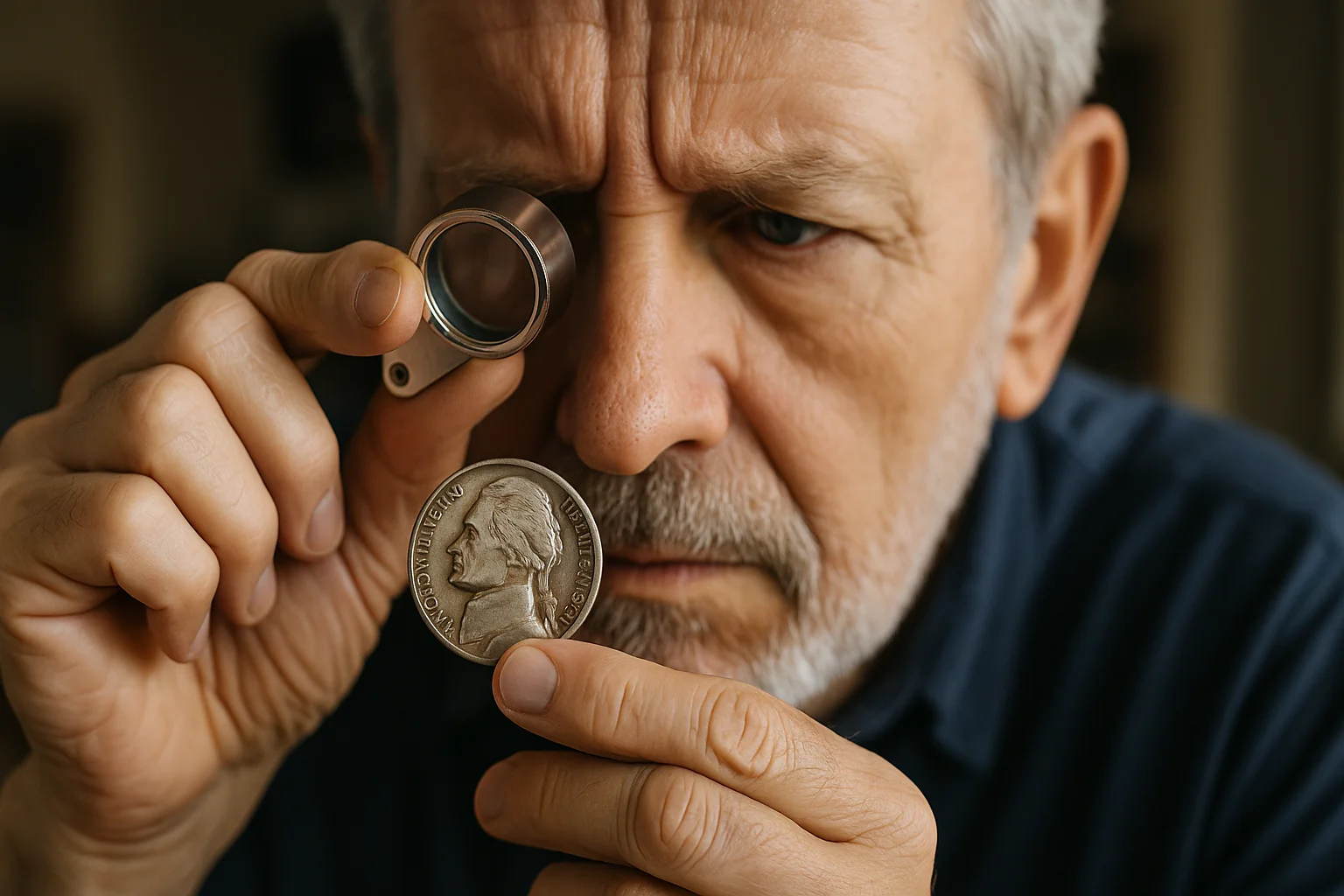

Doubled Dies. Some 1940 nickels show visible doubling on the date or in the lettering around Jefferson’s portrait. These errors happened during the die-making process and are immediately noticeable under magnification. Collectors prize them because each doubled die variety is scarcer than regular strikes, often multiplying the coin’s value several times.

High-Grade Coins. While most nickels from 1940 were heavily circulated, a small number survived in nearly flawless condition. Even a Philadelphia piece without a mint mark (usually considered the most common) can bring a surprising price if it grades Mint State 65 or higher. The sharpness of Jefferson’s portrait and the original mint luster make these coins stand out, especially at auctions.

Full Steps Varieties. On the reverse, Monticello’s steps are a key detail. In most 1940 nickels, the steps were struck weakly and showed wear quickly. Finding one with all six steps sharp and uninterrupted is a challenge, which is why collectors call these “Full Steps” nickels. They often carry a strong premium over regular examples, particularly from the Denver and San Francisco mints.

Practical Advice for Collectors

If you find a 1940 nickel, don’t dismiss it as just another old coin. Check for mint marks, inspect the steps of Monticello, and look for any signs of unusual errors. Even modest upgrades in condition can mean a significant bump in value.

Storage matters as well. Coins kept loose in jars or drawers develop scratches and lose luster. Placing them in coin capsules, cardboard holders, or albums can preserve their surfaces for many years.

Once you know the background of the 1940 Jefferson nickel and the different mint issues, the next step is learning how to evaluate what you have. The process is not complicated, but it does require attention to detail. Four main factors play the biggest role in determining value: condition, mint mark, minting errors, and the rarity of specific die varieties.

The first and most obvious factor is condition, or grade. A coin’s appearance tells the story of how much it has circulated. The better the condition, the higher the value. Instead of describing this generally, here’s a clear table showing how collectors evaluate 1940 nickels:

Grade / Condition | Visual Features | Approximate Value Range |

Good (G-4) | Jefferson’s portrait is heavily worn, major details missing, Monticello flat. | $0.10 – $0.20 |

Fine (F-12) | Jefferson’s profile is visible but soft, lettering clear, Monticello shows wear. | $0.25 – $0.50 |

Extremely Fine (XF-40) | Light wear on cheekbone and steps, most details sharp, some luster remains. | $1.00 – $2.00 |

Uncirculated (MS-60 to MS-65) | No wear, strong strike, mint luster intact, Monticello details sharp. | $4.00 – $20+ |

Tip: Focus on Jefferson’s cheek and the steps of Monticello. If these are flat or blurred, the grade drops quickly.

Not all 1940 nickels are equal, even if they look the same at first glance. The mint mark reveals where the coin was made:

Philadelphia (no mint mark): The most common, as Philadelphia struck the largest number of coins.

Denver (D): Scarcer than Philadelphia issues and generally more desirable.

San Francisco (S): Often carries the highest premium in higher grades, especially when the strike is strong.

Collectors value Denver and San Francisco coins more highly because of their lower mintages compared to Philadelphia. If you spot a “D” or an “S” to the right of Monticello, you already have something more interesting than a typical no-mark example.

Errors add character and can turn a common nickel into a valuable find. For the 1940 Jefferson nickel, several documented mistakes are known, and collectors actively seek them out:

Doubled Die Obverse or Doubled Die Reverse

Some coins show clear doubling on the date “1940” and the word “LIBERTY.” These varieties are rare and can sell for several times the price of a normal coin.

DDR is less common than obverse doubling, but some examples show doubling on “MONTICELLO” and “FIVE CENTS.”

Off-Center Strikes

A portion of the design is missing because the coin blank wasn’t properly aligned. Minor misalignments (5–10%) are modestly collectible, but dramatic off-centers (40% or more) can command strong premiums.

Clipped Planchets

The coin shows a crescent-shaped cut on the edge where the blank was punched incorrectly. These are easily noticeable and popular among error specialists.

Die Cracks

Raised lines across Jefferson’s portrait or Monticello caused by cracks in the minting die. Most are minor, but larger cracks can be collectible.

Tip: Always use a magnifier to check the date, lettering, and Monticello steps. Errors often hide in small details that casual glances miss.

Sometimes value doesn’t just depend on the mint mark but also on the specific die used. A die is the metal stamp that imprints the design on the coin. Over time, dies wear out or get replaced, creating subtle variations between coins struck in the same year and mint.

For 1940 nickels, certain combinations of date size, spacing, and mint marks are scarcer than others. These varieties may not be obvious to beginners, but advanced collectors look for them. While most coins are standard issues, finding a recognized die variety can make your nickel far more attractive on the collector market.

Tip: To better understand the nuances of each coin, refer to the modern tech, for example, to the Coin ID Scanner app. It allows you to photograph your coin and quickly identify its type and approximate value. This is especially helpful for beginners who might not recognize mint mark placements or historical background at first glance.

Evaluating coins can be exciting, but beginners often fall into the same traps. Here are the most common mistakes to avoid:

Confusing mint marks: Many assume that no letter means a misprint, when in fact it simply means Philadelphia.

Thinking every old coin is valuable: Age alone does not equal rarity or high value.

Ignoring condition: Even a rare mint mark loses most of its appeal if the coin is heavily worn.

Poor storage: Tossing coins into jars or boxes leads to scratches and dullness that reduce value.

Collector’s tip: Before you make a decision about selling or trading, use special technologies like the Coin ID Scanner app and compare your coin with certified examples from trusted catalogs or auction sites to receive a realistic picture of its place in the market.

The true value of a 1940 nickel depends on more than its age. Condition, mint mark, striking errors, and die varieties all play a role in determining what collectors will pay. A worn Philadelphia example might only be worth a few cents, while a sharp San Francisco piece with Full Steps can reach far higher.

For anyone with a 1940 nickel in hand, the best strategy is patience and careful inspection. Sometimes what looks like an ordinary piece of pocket change turns out to be a small treasure. With the right knowledge, you can easily separate the common from the exceptional and perhaps find a valuable piece of American history right in front of you.